What’s wrong with the police? For the second time, they have announced they will not be charging anyone over the death of Jai Davis in Otago prison. Davis died two days after he smuggled drugs into the prison by ‘internal concealment’ in February, 2011.

What’s wrong with the police? For the second time, they have announced they will not be charging anyone over the death of Jai Davis in Otago prison. Davis died two days after he smuggled drugs into the prison by ‘internal concealment’ in February, 2011.

At the coroner’s inquest in November last year, Detective Inspector Steve McGregor said charges against Corrections officers had been considered – for manslaughter and criminal nuisance – but eventually claimed the evidence didn’t meet the threshold for a successful prosecution.

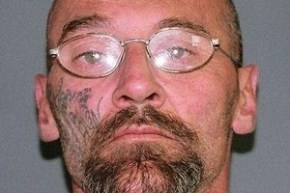

In reality, there is no threshold – the Solicitor General just made that up. But after the inquest, Inspector McGregor announced police would reconsider their decision not prosecute. Today, two months later, the coroner, David Crerar (right), announced the police have advised that no charges will be laid afterall. It seems the evidence still doesn’t meet the non-existent ‘threshold’.

The prison protocol

How is this possible? The Corrections Department has a written protocol called: “Management of prisoners suspected of internally concealing unauthorised items”. It says that the prisoner should be placed in a ‘dry’ cell – one without a toilet. When the prisoner needs to ‘go’, they give him a cardboard potty. Officers then examine the contents so they can retrieve the drugs and charge the prisoner with bringing in the ‘unauthorised item’. The policy also says that “a Medical Officer must be informed”. The reason is obvious – a prisoner with drugs inside might die. He needs to be examined and, if necessary, sent to hospital for an x-ray.

The Customs Service has a similar protocol and they advise that “no person has ever died while being detained by Customs” when following this policy.

Three prison managers involved

In Davis’ case, there were at least 20 employees at the Otago prison who ignored the protocol. Three of them were prison managers. The most senior was acting prison manager, Chris Gisler, who had been with Corrections for 21 years. Believing that Davis would be concealing drugs when he arrived, Gisler gave the order to segregate him in a dry cell ‘for the purpose of security, good order, or safety of the prison’ under section 58 of the Corrections Act. He probably could have saved Davis’s life by using section 60 of the Act – ‘segregation for the purpose of medical oversight’. But he didn’t think of that.

Gisler was off duty when Davis was brought in so he delegated the task to Operations Manager Ann Matenga and Security Manager Michael Fitzgerald. On Friday 11th February, 2011 when Mr Davis arrived at the prison, Ann Matenga signed the segregation order stating:

“I will notify the Medical Officer of the prison of this segregation within the applicable timeframe after the above named prisoner is placed in a cell…”

The applicable timeframe was three hours. Ms Matenga was on duty all weekend but never called the doctor. At the inquest she claimed she didn’t know that ‘medical officer’ meant ‘doctor’.

Michael Fitzgerald was the Security Manager. He briefed the security team that Davis was coming in with drugs on board. One of his team then went to the prison health centre and advised the nurses on duty of the situation. The reality was that Gisler and Fitzgerald were totally focussed on security issues – preventing Davis passing the drugs to other prisoners – so they didn’t even think about calling the Medical Officer. Nor did they check with Ann Matenga to see if she had done so. Not one of these three managers thought it necessary to advise the prison doctor that a man was being brought in who was at risk of dying from a drug overdose. It wasn’t even discussed.

Six prison nurses involved

Six different nurses were on duty over the weekend – three of them on the day Davis died. They all knew Davis was in the dry cell because he was suspected of concealing drugs internally.

None of them called the doctor – not even on the Sunday morning when the prison officers on duty noticed Davis had deteriorated and looked seriously unwell. So unwell, that one said:

“He looked like a corpse. His eyes were sunken and he had the cold sweats. .. his breath smelt like faeces… and he had slurred speech as well. He looked as though he should have been in hospital.”

Because the officers were concerned, nurses checked on Davis three times that morning but did nothing. One of them, Gayle Catt, told Corrections Inspector David Morrison, that…

“(Davis) seemed to slightly deteriorate from 7-30 to 8-30am. My concern was that he would go unconscious but officers would think he was asleep.”

Three years later at the inquest, she’d forgotten she said this and claimed: “He was well; he was absolutely well every time I saw him. I had no concerns about his physical safety whatsoever.”

Then there’s Janice Horne, the last nurse to see Davis alive. She was on the afternoon shift on Sunday and only went to see Davis once in her eight-hour shift – at about 4 p.m. Even then, she didn’t go into his cell to examine him. She spoke to him though a small flap in the cell door. Afterwards, she made an observation in his Medical notes that he appeared to be under the influence of drugs…

“because of the slow movements that he was making… she had a conversation with the unit officer where she stated to the officer, Mr Davis ‘looks stoned’.”

Nurse Horne didn’t seem to realise how serious the situation was. She carried on with her other duties, knocked off work at 8 p.m. and went home. Davis appears to have died two hours later. His last recorded movement on the CCTV tape occurred at 10.01pm. A few months after Davis died, Janice Horne resigned and went to live in Australia.

The health centre manager

Despite the risk posed by internally concealing drugs, not one of the six nurses on duty over the weekend called the prison doctor. Not one of them even bothered to consult with the health centre manager, Jill Thompson, who was the head nurse. If they had, Ms Thompson could possibly have saved Davis’ life. When she was interviewed after his death, she said:

“As there was clear knowledge that this person was concealing drugs, why did he come here in the first place? The prison is 45 minutes away from a hospital. If drugs had exploded in a prisoner’s gut, we would not be able to get (him) to the hospital in time…”

That’s her clinical opinion on what should have happened. But it didn’t happen – because Jill Thompson wasn’t at work on the Friday afternoon when Davis was brought in. She wasn’t away at a managerial seminar. She wasn’t sick. Three years later when asked by lawyers at the inquest where she was on that Friday, Ms Thompson claimed she didn’t remember.

The police didn’t seem to realise the significance of Jill Thompson’s unauthorised absence. In the course of a three year investigation, they never even asked her where she was that day. Perhaps she went shopping. The point is she abandoned her legal duties and Mr Davis died. That’s called negligence and it’s potentially a criminal offence. But Ms Thompson was never prosecuted. She didn’t lose her job. She wasn’t reprimanded by Corrections. She wasn’t even questioned by police.

Ten prison officers involved

At least ten Corrections officers were also aware that Davis had drugs on board – and could have called the doctor. Five of them escorted Davis from the prison gate to the At Risk Unit. One of them, Chris Dalton, wrote on Mr Davis’s At Risk management plan “information received from operational intelligence unit that prisoner is concealing drugs on person.” He told police it was his role to ensure the safety of both staff and prisoners and “if anything needs to be done when there is no manager, it falls upon me to action that request.” There was no manager, at least no health centre manager. But Dalton didn’t call the doctor either.

Another officer, James Neill testified that he was briefed by security manager Michael Fitzgerald. He said he then went over to the prison health centre and advised two nurses that “a prisoner was coming in suspected of concealing drugs”. Mr Fitzgerald showed one of the nurses a document titled “Advice to Prisoner Suspected of Concealing” and said “a medical officer is required to sign it.” But the medical officer wasn’t there. Mr Fitzgerald took the form away – so no one signed it. (The medical officer was hardly ever there. See Prison deaths linked to Corrections refusal to employ sufficient doctors.)

There were also half a dozen other prison officers on duty in the At Risk Unit on the day Davis died. Two or three of them were concerned that Davis had deteriorated and should have been taken to hospital. But none of them made the call – they all thought it was the nurses’ job.

The police have a job too – to prosecute those responsible when their negligence contributes to someone’s death. At the inquest, Senior Sgt Colin Blackie who conducted the police investigation, gave the impression that, at the very least, he would have prosecuted some of the nurses. But he was taken off the case. The harsh reality is that no one in the Corrections Department has ever been prosecuted over a so-called ‘unnatural death’ in prison.

other 90 unnatural deaths

other 90 unnatural deaths