Familicide is the name given to a particular kind of multiple murder – where one member of a family kills virtually everyone else in the family. If the perpetrator commits suicide afterwards (which occurs in 60% of such cases), it is referred to as familicide-suicide.

Familicide is the name given to a particular kind of multiple murder – where one member of a family kills virtually everyone else in the family. If the perpetrator commits suicide afterwards (which occurs in 60% of such cases), it is referred to as familicide-suicide.

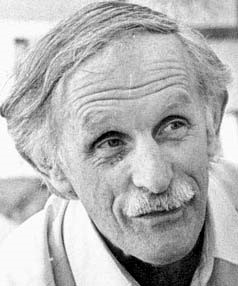

In June, 1994, David Bain was accused of shooting all five members of his family – the crime of familicide. He was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison – although according to Canadian judge Ian Binnie ‘no plausible motive ever emerged’. He spent 13 years in prison before a retrial, at which he was found not guilty.

Throughout this process, David’s defence team argued that Robin Bain killed his wife and children while David was out delivering newspapers; that he typed the cryptic message found on the family computer (‘Sorry. You are the only one who deserved to stay’) and then shot himself – in a case of familicide-suicide.

Binnie said David should get compensation. The Government didn’t like that idea and shopped around for another judge – one who was willing to write a report declaring that David didn’t deserve it. They found one in Ian Callinan QC, who had a history of bending the rules in Australia.

So far, not much has been reported in the New Zealand media about Callinan’s dodgy legal ethics or the extraordinary flaws in his compensation report. But there’s a wealth of information available on the David Bain Campaign website.

Familicide

But there’s another side to this story which has not seen much daylight either. A systematic review of the literature on familicide found a number of common factors in such incidents. The first is that in 95% of cases where both parents were killed, the perpetrator was the father. Only 1% of familicides are committed by an adult son. The researcher wrote:

“In cases where (one of the) sons killed both parents, the research indicates that the perpetrator is always either severely abused, suffering from severe mental disorders (usually psychotic) or psychopathic. There are no identified cases where the son exhibits none of these pathologies and does not commit suicide.”

Second, many of these fathers displayed symptoms of depression prior to the killings and a number of Robin Bain’s professional colleagues testified to this effect. Fellow teachers described Robin at the time of the killings as “deeply depressed, to the point of impairing his ability to do his job of teaching children”.

He also published graphic and inappropriate stories of violence and killings by his 9-year-old pupils in the school newsletter; one of those stories involved the murder of an entire family. The president of the Taieri Principals’ Association at the time, found this “unbelievable” and regarded the publication of these stories as “the clearest possible evidence that Robin Bain had lost touch with reality due to his mental state” (Privy Council, 2007, para 41). The publication also suggests Robin had possibly been planning to kill his family months in advance.

It appears Robin Bain never sought professional help for depression, but this is another point of commonality; fathers who commit familicide tend to view themselves as the head of the family, and “control their outer image closely, rarely confiding in people or seeking help”. The fact that family and friends said Robin appeared to be happy is consistent with other familicides; such men internalise their personal sufferings in order to maintain appearances.

Angry vs despairing perpetrators

The literature also suggests there are two types of familicide perpetrator. At one end of the continuum, there is the angry type – men who have displayed a well-established history of anger and hostile behaviour, especially towards women. For this type, the killing of one’s partner and children is an act of revenge or punishment, usually following parental separation. At the other end of the continuum, there is the despairing type of perpetrator who has no previous history of hostile behaviour and is generally well regarded in the community. This description applies to Robin Bain. For this type, familicide, followed by suicide is “an escape both for himself and his family from an intolerable future”.

In addition to feelings of depression and anger, the literature shows that familicide is generally preceded by a prolonged build-up of shame. This usually follows parental separation or a serious breakdown in the relationship; loss of employment or significant financial losses may also be involved. These lead to a psychological loss of control and/or a perceived loss of social status. Robin Bain also fits this profile. He and Margaret had been estranged for several years and by all accounts, he was unfulfilled in his job. He had applied for a number of other teaching positions, but was unsuccessful.

But for Robin Bain, there may have been an even greater source of shame. He was a Christian, a Freemason and a respected member of the community. At the second trial, witnesses said he had been committing incest with his youngest daughter, Laniet, ever since the family came back from Papua New Guinea. If indeed he had been molesting her, this would have created intense feelings of guilt and internal conflict. It seems that “despair is the end-state for these perpetrators”.

The triggering event

The research also found that in most cases of familicide there is usually some kind of triggering event, one which leads to a sense of “ignominy, terminal public shame, mortification and self-disgust”. Testimony at the second trial suggests Laniet was about to reveal to the rest of the family what her father had been doing to her. It seems the potential loss of face Robin Bain was facing was so great, he not only killed everyone else in the family (except David), he also shot himself. This is another point of commonality. In over 60% of familicide cases, the offender subsequently commits suicide.

In summary, David Bain did not have an identified motive, did not have a mental health disorder and did not commit suicide. Robin Bain did, or had, all three. In every single aspect of this case, it is Robin Bain rather than David Bain, who fits the profile of the typical perpetrator of familicide, followed by suicide.