News that Gavin Hawthorn has recently been convicted of drink driving yet again has caused oodles of outrage in the media. Hawthorn has already killed four people in two separate accidents. In 2004 he was convicted of manslaughter over the death of his friend Lance Fryer and sentenced to 10 years in prison. He was released in 2013 and has now been caught drink-driving again – for the 13th time. On this occasion Judge Johnston sentenced him to six months home detention and disqualified him from driving for two years.

The headlines were horrified. Stuff stated it like this: Recidivist drink-driver Gavin Hawthorn convicted again, leading to call for permanent driving ban. Newshub harrumphed that it was ‘Appalling’: Porirua man Gavin Hawthorn escapes jail after 12th drink-driving conviction. The Herald highlighted: NZ’s worst drink driver caught drunk behind the wheel again. Duncan Garner was especially incensed arguing that:

“This judge has failed to keep us safe as New Zealanders. We’ve been let down by his profession once again. He has let us down, now we are in harm’s way.” He went on to say the case was an example of why the public “have little confidence in the justice system”.

Blaming judges is misguided and myopic. This is what Garth McVicar and the senseless sentencing trust have been doing for years. All that has achieved is a burgeoning prison population and a crisis in capacity. At $100,000 per prisoner, per year and a reoffending rate of 60% within two years of release, clearly this is a failed strategy – and a massive waste of taxpayer money.

Keeping us safe

The justification for all this moral outrage is the dubious assumption that sending ‘dangerous’ people to prison ‘keeps us safe’. Does it? Let’s look at the facts.

Gavin Hawthorn killed his last victim in 2003. Between 2003 and 2017, another 5,402 people have died on New Zealand roads – an average of 360 people a year – or nearly one every day. Half of these deaths are caused by drivers under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or both.

The point is that most of these people died during the ten years that Hawthorn was in prison. Clearly his incarceration did not make us any safer. Giving the judge a hard time for not sending him to prison on his current conviction does not change this reality.

So, what’s the solution? The only intelligent comments in the media came from Andrew Dickens on NewstalkZB who asked rather quaintly: What to do with our drinkiest drink driver? He argued with considerable insight that:

“Indefinite incarceration and licence deprivation is not what this man needs. What he needs is to STOP FREAKING DRINKING.”

Drug courts

Dickens’ answer to the problems posed by the likes of Gavin Hawthorn is to put him into a drug court (in New Zealand known as AODTC – Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Courts). To be eligible, defendants must be alcohol or drug dependent and facing a prison sentence. A treatment plan for each participant is developed by the judge, taking into account the views of treatment providers, support workers and lawyers; it involves rehabilitation, counselling, drug-testing, community service and making amends to victims.

Dickens describes the process like this:

“They’re a three-phase, 18-month-long programme designed for high-needs and high-risk addicts who are facing prison, or who have tried but failed treatment programmes in the past.”

Drug courts have the potential to help thousands of offenders, not just drink drivers. And there is no shortage of available candidates in New Zealand. In 2011, judges told the Law Commission that 80% of all offending was alcohol and drug related. In 2017, Northland district court judge, Greg Davis, who sees a lot of methamphetamine related crime, said up to 90% of all offending was related to issues with addiction.

Currently, the only two drug courts in the country are both in Auckland. Hawthorn is serving his sentence of Home Detention in Paraparaumu – so a drug court in Wellington would be helpful. We need such courts in all our major cities.

Compulsory AOD assessment

Another strategy is available to target drink drivers in particular – one that also involves assessment and treatment. Currently out of 20,000 people convicted of this offence each year, only 5% – those disqualified indefinitely – are required to have an alcohol and drug assessment to see if they have their drinking under control before getting their driver’s licence back. Many of the remainder are sent to prison – just like Gavin Hawthorn. If any drink driver who incurred a second conviction was required by law to have an AOD assessment before their disqualification could be lifted, fully half of the 20,000 drink drivers would be assessed. As a result, there would be a lot less people in prison.

An evaluation of the NZ drug courts shows they also reduce imprisonment – 282 participants have been kept out of prison during the six years the two Auckland courts have been operating.

So if the government implemented these two strategies, this would shift the focus of our justice system away from punishing alcohol and drug addicted offenders towards treating them instead. This would surely help Justice Minister, Andrew Little, get closer to the Government goal of reducing the prison population by 30%. Maybe it would even moderate the media to tone down their moral outrage.

The population peaked in March at 10,820 and on 3 October had dropped to 10,035 – a 7.3% fall.

The population peaked in March at 10,820 and on 3 October had dropped to 10,035 – a 7.3% fall.

One TOP party policy that hasn’t received much attention in the run up to the election is Gareth Morgan’s wish to reduce the prison population. He

One TOP party policy that hasn’t received much attention in the run up to the election is Gareth Morgan’s wish to reduce the prison population. He

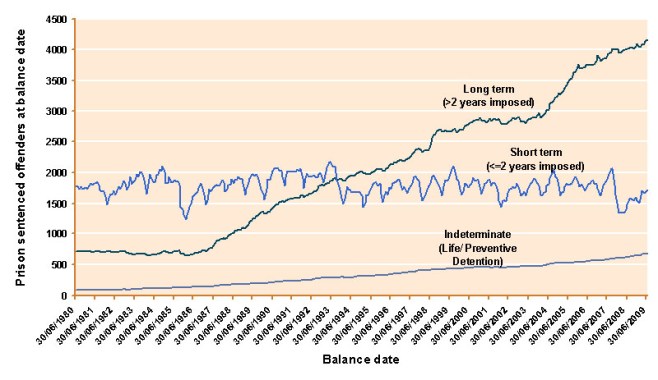

No – we don’t. There is absolutely nothing inevitable about this increase in our prison population. It is entirely the result of penal policies passed by both Labour and National governments in the last few years – policies which have been getting more and more draconian. In a press release in 2002,

No – we don’t. There is absolutely nothing inevitable about this increase in our prison population. It is entirely the result of penal policies passed by both Labour and National governments in the last few years – policies which have been getting more and more draconian. In a press release in 2002,

The reason is obvious. Those who end up in prison tend to come from backgrounds of deprivation and abuse, and suffer from mental health problems and addictions. A useful analogy is that are emotionally and socially crippled – the psychological equivalent of having two broken legs. Rehabilitation in prison is akin to placing a plaster cast on one leg. The other leg only gets a plaster cast when the prisoner is released – in the process of reintegration.

The reason is obvious. Those who end up in prison tend to come from backgrounds of deprivation and abuse, and suffer from mental health problems and addictions. A useful analogy is that are emotionally and socially crippled – the psychological equivalent of having two broken legs. Rehabilitation in prison is akin to placing a plaster cast on one leg. The other leg only gets a plaster cast when the prisoner is released – in the process of reintegration. The same coroner

The same coroner