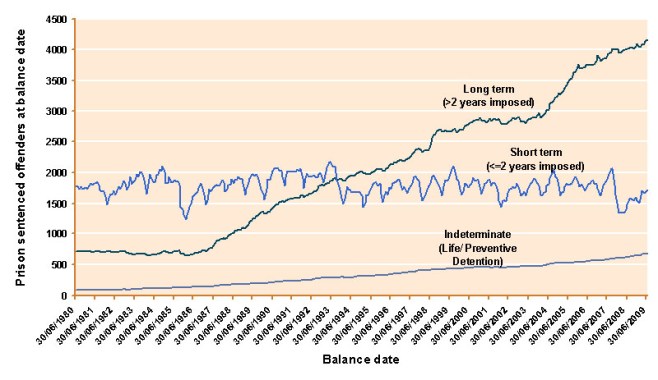

In 1985, there were 2,775 prisoners in New Zealand. On 29 November 2016, Corrections Opposition spokesperson, Kelvin Davis (now the Corrections Minister), posted a message on his Facebook page stating that the muster had just passed 10,000 – an increase of 364% in 30 years – and the National Government was planning to build a new prison. Davis wrote:

We’re spending a billion dollars to build a new prison and I have just one question: what happens when that is full? Build another? That will be another billion bucks poured down a bottomless hole.

The reality is that the prison population had been on the rise for 70 years and was projected to hit 12,000 by 2022. Kelvin Davis and the Labour team aren’t keen on building an expensive new prison every three years so when the current coalition government took over, Justice Minister, Andrew Little announced he intended to reduce the prison population by 30 per cent over the next 15 years.

It’s not that hard

Little even said “It’s actually not that hard if we choose to resource it properly.” The prison population at the time was 10,394. Two years later it’s still at 10,200, which the NZ Herald described as a prison system bursting at the seams.

So despite Andrew Little’s claim that reducing the prison population is “not that hard”, the coalition government has made no progress towards that goal whatsoever – we still have over 10,000 people in prison. But to give credit where credit is due – at least the muster has stopped going up – for the moment.

The Corrections Department clearly does not expect this pause in the upward trajectory to last. In response to an OIA, Corrections advised that, even though they are not building a new prison, they are in the process of expanding capacity at eight existing prisons using Chinese made modular (prefab) ‘rapid deployment cells’ – although according to Corrections Association president, Alan Whitley, the deployment has been far from rapid.

The extra beds will be at the following prisons and cost $406 million:

| Prison | New beds |

| Rolleston | 244 |

| Tongariro | 122 |

| Christchurch Womens | 122 |

| Christchurch Mens | 244 |

| Rimutaka | 244 |

| Total new beds | 976 |

Three other “prisons also have capacity projects in progress” budgeted at $916 million. Corrections claims the new beds in these three prisons “do not all represent expansions” as these new units will allow older units at these prisons to be disestablished. Obviously, older units are unlikely to be disestablished if there is a blowout in inmate numbers.

| Prison | New beds |

| Waikeria | 600 |

| Mt Eden | 318 |

| Arohata | 69 |

| Total | 987 |

Total new prison beds

Altogether, the Government is adding a total of 1,890 new beds. Currently, each of the four largest prisons in the country holds approximately 950 prisoners. By adding another 1,890 beds, the Government is surreptitiously constructing the equivalent of two large prisons – at a cost of just under $1.5 billion. This covert expansion in prison capacity highlights the hypocrisy of Kelvin Davis’ hope that Labour would do things differently.

I agree with Andrew Little that reducing the prison population is not that difficult. But to do so requires legislative changes such as repealing the disastrous Bail Amendment Act which doubled the number of prisoners on remand within two years. The problem is that to pass the necessary legislation, Labour requires support from NZ First – and when Andrew Little proposed repealing the repugnant three strikes law, Winston Peters rapidly pulled the rug out from under his feet.

The coalition agreement

The problem is that when the Labour Party went into this alliance with New Zealand First, it failed to make justice and prison reform a part of the coalition agreement. The only law and order related issue in the agreement was to:

Strive towards adding 1800 new Police officers over three years and commit to a serious focus on combatting organised crime and drugs.

Not only did Labour fail to address prison reform with its coalition partners when forming a government, nor did it seek cross-party agreement with the National party on any of these issues. Given that National takes a ‘tough on crime’ law and order approach (which inevitably involves building new prisons), establishing a 15-year goal without cross party agreement is unbelievably naive. New Zealand has a three-year election cycle. Labour would have to win five elections in a row to make progress towards such a long-term goal.

You can’t win with two captains

Since we’re all Kiwis, let’s use a sporting analogy. Setting a 15-year goal to reduce the prison population by 30% without cross-party agreement is like playing an endless game of rugby without a referee. When they get possession of the ball (i.e. the power to govern), each side just does whatever it wants. The goals and strategies of previous governments are cast aside.

Similarly, a coalition agreement with New Zealand First which does not include an agreement to reform the justice system is like an All Black team with two captains (in this case, Jacinda and Winston). Jacinda captains the forwards and they want to attack (to reform the justice system and reduce the prison population). Winston captains the backs and when it comes to law and order, he just wants to play defence (and lock em up). When the backs and the forwards have different captains and opposing strategies, it’s a struggle to move the ball forward, let alone score a try.

This situation highlights the difficulty of introducing radical reform in a democracy with elections every three years. 90% of democratic countries have four or five-year terms which give governments more time to make changes. And the prison population could be reduced by 50% within five years. But even that wouldn’t solve the problem facing Jacinda Ardern when the other captain is constantly undermining the team.

The lesson that Labour should learn from this is that they should have been a lot tougher negotiating with Winston Peters before they got into bed with him and agreed to form a team (apologies for the mixed metaphors). In the justice arena, getting into bed with Winston has been an abortion – with billions still getting poured down a bottomless hole.

Criminology graduates and a senior criminology lecturer at VUW are calling for the Climate Change Amendment Bill currently before Parliament to be totally transformed so that it reflects the reality that the world is facing an existential crisis.

Criminology graduates and a senior criminology lecturer at VUW are calling for the Climate Change Amendment Bill currently before Parliament to be totally transformed so that it reflects the reality that the world is facing an existential crisis.

Generally, police pursuits in New Zealand do not involve such serious crimes or such dangerous offenders. Since January 2008, police have pursued over 30,000 fleeing drivers leading to

Generally, police pursuits in New Zealand do not involve such serious crimes or such dangerous offenders. Since January 2008, police have pursued over 30,000 fleeing drivers leading to

What happened to the fundamental legal principle: Innocent until proven guilty? Perhaps Andrew Little is right – our justice system is broken – we lock up way too many people who have yet to be convicted of a crime. Isn’t that what third-world dictators, communist countries and authoritarian, anti-democratic regimes do?

What happened to the fundamental legal principle: Innocent until proven guilty? Perhaps Andrew Little is right – our justice system is broken – we lock up way too many people who have yet to be convicted of a crime. Isn’t that what third-world dictators, communist countries and authoritarian, anti-democratic regimes do?

The population peaked in March at 10,820 and on 3 October had dropped to 10,035 – a 7.3% fall.

The population peaked in March at 10,820 and on 3 October had dropped to 10,035 – a 7.3% fall.