Rehabilitation in prison: numbers attending drops by 75%, while the cost triples

In 2017, 10,400 offenders attended a rehabilitation programme offered by the Corrections Department (see chart below.) This includes offenders in prison plus offenders on community sentences. The cost to the taxpayer that year was $180 million. That’s $17,307 per offender. In 2023, 5,601 offenders attended rehabilitation at a cost of $346 million. That’s $61,774 per offender.

In other words, between 2017 and 2023, the number of offenders attending rehabilitation has halved while the cost per offender has more than trebled.

Number of offenders attending rehabilitation programs each year (and the cost)

| Year | Number of prisoners | Number of offenders in the community | Cost (Millions) from Annual Reports |

| 2017 | 7,200 | 3,200 (p.98) | $180.8 (p.99) |

| 2018 | 6,766 | 2,798 (p.94) | $215.7 (p.98) |

| 2019 | 4,806 | 4,094 (p. 52) | $243.1 (p.87) |

| 2020 | 3,738 | 3,199 (p.62) | $266.3 (p. 99) |

| 2021 | 3,687 | 4,064 (p. 72) | $296.8 (p.99) |

| 2022 | 2,086 | 2,271 (p. 70) | $322.2 (p.113) |

| 2023 | 2,631 | 2,970 (p.79) | $346.5 (p.198) |

| 2024 | Not published | Not published | $376.1 (p.182) |

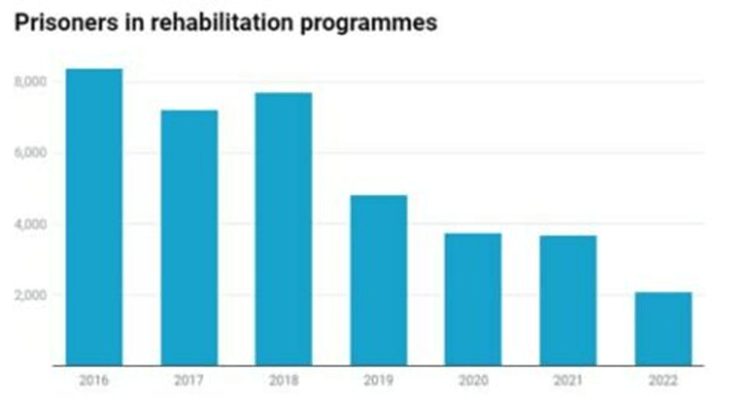

The number of prisoners (excluding community based offenders) attending rehabilitation programs has dropped by an even greater margin – to one quarter of the number attending in 2016. See chart below (Corrections figures published by NZ Herald.)

Corrections rehabilitation programs almost totally ineffective

Making matters worse, these programmes have become increasingly ineffective. Every year, Corrections publishes a report describing the extent to which each of its rehabilitation programs reduce reoffending – based on results in the first 12 months after participating prisoners are released.

In 2017, the Department’s Annual Report listed 13 different prison-based interventions. The average reduction in reoffending across all 13 programmes was only 3.9%. The best performing programme (for Violent Offending) reduced reoffending by 10.4% in the following 12 months. However, very few inmates are referred to this program.

The Annual Report for 2024, shows that Corrections offered only eight programmes in prison. The average reduction in reoffending almost halved to 2.3%. Three of those programs target offenders with addictions – in Drug Treatment Programs (DTP). Rather than reducing reoffending, in 2024 the DTP actually led to an increase (Annual Report, p. 196).

Misinformation published by the Corrections Department

Corrections has a history of publishing grossly exaggerated statements about the effectiveness of its rehabilitation programs in order to persuade whichever Government is in power at the time to continue funding them. For example:

- “Most of what we are doing to reduce re-offending succeeds.” Dr Peter Johnston Director Analysis and Research, Department of Corrections. The New Zealand Corrections Journal, July 2017.

- “The Department has been achieving very promising gains though these programmes.” Dr Peter Johnston Director Analysis and Research, Department of Corrections. The New Zealand Corrections Journal, November 2018.

- “New Zealand remains the only country in the world that routinely measures and reports on the outcomes of the full suite of its rehabilitative interventions. The process has major benefits in enabling us to direct, and re-direct, resources to where we get best effects, to improve effectiveness, and to avoid wasted effort.” Dr Peter Johnston Director Analysis and Research, Department of Corrections. The New Zealand Corrections Journal, July 2017.

None of these statements published by the Corrections Department are true.

Rehabilitation in the AODTC

The only intervention available in New Zealand which makes a significant difference is the Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Court (AODTC). Not only does it reduce reoffending, it even keeps high risk offenders out of prison, saving millions in court, police, prison and health costs.

There are two such courts in Auckland and one in Hamilton. Between 2012 and 2018, the AODTC was evaluated more extensively than any other justice related intervention in New Zealand history. The Ministry of Justice found it reduced reoffending of graduates by 86% more than a matched group of offenders. This result is 86 times better than drug treatment in prison in 2024. Those are the facts.

Andrew Little was a member of Parliament when these evaluations were being conducted. In 2017, he became Minister of Justice and was so impressed with the early results, he said drug courts would be “rolled out across New Zealand in 2018”. Each court costs about $3 million a year to operate. But since the drug court was established in Hamilton, no funding has been made available to roll them out anywhere else. Why? Because the Ministry of Justice misled Andrew Little and Cabinet about the remarkable effectiveness of the AODTC, and has consistently lied to Cabinet about the benefits of rehabilitation in prison.