The previous Labour government set a goal to reduce the prison population by 30% – and in March 2022, it dropped to 7,677. Chris Luxon became Prime Minister in 2023. Within a year, the prison muster passed 10,000. In November, 2025 it surged to nearly 11,000.

Luxon described this as “absolutely a good thing,” and was unconcerned about the cost. He said: “I understand… the financial implication of… restoring law and order. The cost will be what the cost will be.”

In 2024, Corrections cost the taxpayer over $2.8 billion. Perhaps Luxon doesn’t care, but when other justice sector agencies such as police and courts are included, the total cost of ‘law and order’ comes to $7.3 billion a year. So he should care.

This is why.

1) First, the lock ‘em up approach he advocates is based on a decidedly dodgy theory known as deterrence – that the fear of being incarcerated, will deter people from committing crime – and having spent time in prison will deter them from further offending.

New Zealand’s recidivism rate provides ample proof this theory doesn’t work – prisons are more like universities for crime. Incarceration takes offenders off the streets temporarily, but just about everyone gets released eventually.

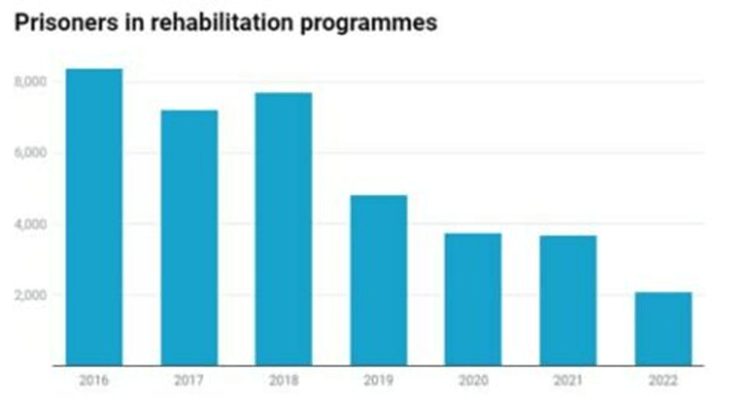

2) Second, very little rehabilitation is available in our prisons. Between 2016 and 2022, the number of prisoners attending rehabilitation programmes declined from over 8,000 to around 2000.

3) Third, these prison programmes are almost totally ineffective. In 2021, Corrections’ Annual Report listed 23 different prison-based interventions intended to reduce recidivism. The average reduction in reoffending was only 2.3%. The best performing programme (prison-based employment) reduced reoffending by 4.3%. In 2024, Corrections offered only eight prison-based interventions. The average reduction in reoffending was 2.6%.

4) Fourth, even though these programmes fail to reduce reoffending, Corrections demands more funding for them every year. In 2016, Corrections was allocated $180 million “to reduce reoffending.” In 2026, the Department was given $420 million. In other words, the cost of rehabilitation has more than doubled in the last ten years while the number of prisoners attending these programmes has dropped by 75%. That’s money down the drain.

Flawed research by Corrections and MOJ

There’s another reason why governments have been so willing to squander taxpayers’ money on prison programmes. Both Corrections and the Ministry of Justice insist on telling whichever Government is in power that it is money well spent. In 2017, Dr Peter Johnston, Director Analysis and Research for Corrections pretended: “Most of what we are doing to reduce re-offending succeeds.” In 2018, he claimed“The Department has been achieving very promising gains though these programmes.” These are gross exaggerations – refuted by the Department’s own research.

In 2022, the Ministry made similarly outrageous claims in its Long Term Insights Briefing on Imprisonment 1960 to 2050. This 120-page document presented to Parliament, said “prison-based rehabilitation programmes have consistently delivered better results than community-based programmes in New Zealand.”

86% reduction in reoffending in the AODTC

The Ministry is well aware this is not true. In 2019, it published an evaluation of the Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Court (AODTC) in Auckland. The AODTC treats high risk, high needs recidivist defendants whose crimes are driven by addictions. The Ministry found the AODTC reduced the reoffending of graduates by 86% and kept them out of prison – saving a minimum of $200,000 per defendant. This makes the AODTC at least 40 times more effective than Corrections’ prison-based programmes.

It seems the Ministry doesn’t want anyone in Government to know about the effectiveness of the AODTC. The Long Term Briefing has a chapter titled: “What works to keep people out of prison.” Even in this chapter, the Ministry ignored its own research and omitted any mention of the AODTC at turning around the lives of drug addicted criminals, and keeping them out of prison.

Show me the money

Currently, New Zealand has only three drug courts – in Auckland, Waitākere, and Hamilton. Each court costs about $3.5 million a year to operate. To give each defendant sufficient attention, judges work with a maximum of 50 participants at a time. If Luxon took $100 million out of Corrections rehabilitation budget and used it to set up more drug courts, we could have another 25. Alternatively, he could use the $105 million seized by police in 2025 under the Criminal Proceeds (Recovery) Act.

If each of the 25 courts kept 50 defendants out of prison, that would reduce the prison population by 1,400 in one year. At $200,000 per prisoner, that’s a potential saving of $280 million. And that’s just the potential savings that would be made by Corrections. There would also be massive savings from reduced costs to victims, reduced police costs, reduced court costs and so on.

By keeping all these high risk, high needs offenders out of prison, we might even achieve Labour’s goal of reducing the prison population by 30% – and keep it there. If that saves taxpayers’ money, surely Mr Luxon that would be: “Absolutely a good thing.”